Environmental Art & Design Prize 2021

Non-Objective Art and Environmentalism

A question was posed to me the other day regarding the capacity of non-objective artworks to reflect environmental issues. Ten years ago, I asked myself the same question believing passionately in both the environment and art. This question prompted my return to formal studies and has driven aspects of my practice ever since. I believe that a major problem when addressing issues such as climate change, is the difficulty many people have perceiving specific connections between abstract entities, such as statistics, and the reality they represent. For these people, no matter how accurate the statistics or abundant the evidence, without direct experience the disappearance of a species or quantities of carbon emissions remains an abstract concept and therefore beyond their control. Non-objective Art joins the conceptual with the concrete and demonstrates how abstract entities can relate to the real world, concurrently highlighting the interconnected nature of existence.

Non-Objective, Abstract or Concrete Art, three terms amongst many others that refer to non-representational artworks, have their own unique language, a formal language of constructed, objective and subjective relationships. Non-Objective Art relishes paradoxes and despite its abstract appearance is firmly rooted in reality, the reality of tangible experience. It limits definitive references to the real world in order to expand our conception of reality to include complex, immaterial and philosophical questions about the nature of art and existence. Rather than holding a mirror to reality it creates the relationships from which experience springs. In so doing, non-objective artworks develop one’s capacity to empathetically decipher, physical and intellectual connections to the world we exist within. The artworks can be both personal and universal, rational and organic, planned and serendipitous.

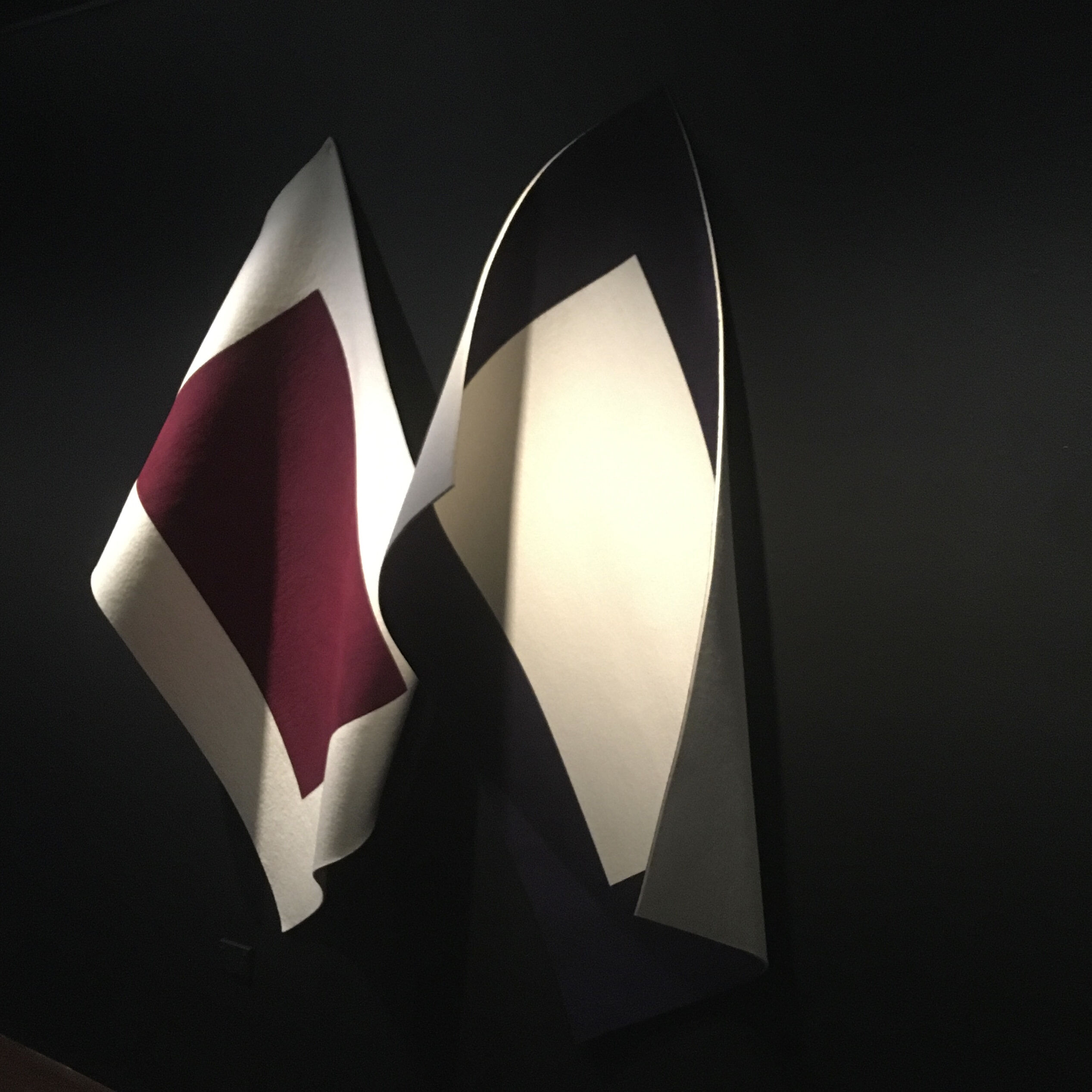

I would describe my artworks as pertaining to an organic realism. Creating provisional, temporary artworks, along with the employment of natural and modest materials, has been a way for me to counteract the environmental impact of my art practice and the accelerating consumerism of society. The artworks stand against the increasingly grand scale of artworks presented as a measure of artistic worth and the Disney-like interaction of art as entertainment. Instead, they require the audience to slow down and engage with the artworks in a process of active, felt, observation. Through a reflective, aesthetic encounter, these artworks demonstrate how one is not outside of nature looking in, but a mutual participant deeply embedded within it. Therefore, every decision we make affects that same environment.

Just because an artwork uses a non-literal language does not mean that it can’t be related to actual issues—be they political, environmental, emotional or other. One only has to look at the inception of Non-Objective Art to understand the ways in which artists believed their artworks capable of expressing political, utopian and revolutionary ideals. For me I use a natural material which can be composted if needed; not all my works are for sale instead partaking in an extended experimental process and standing against mass consumerism; they are intrinsically connected and indebted to nature as their resting forms are dictated by gravity; their delicate fixings are designed specifically to contrast with their dense materiality to empathetically reflect the strength and fragility of organic systems; they form endless relationships mirroring the interconnected nature of existence; they promote focused observation through their materiality and suspension of movement; they respond to changes in the atmosphere and can be rearranged, rehung and manipulated to adapt to different situations. Their provisional and organic nature highlighting our own experience of impermanence and the delicate balance of forces within the natural environment.

The threat of consumerism brings into question the very role of an artist: creator or co-contributor? Yet the role of the artist as social commentator remains valid, and the expression of beauty is still a reminder of what is important to preserve and what is important to feel. Non-objective artworks offer a different perspective on reality despite their abstract appearance. They highlight the ambiguous complexity of human experience.

Below are two early examples of the diversity of artists and their practices that have utilised conceptual means to voice their political and/or environmental concerns:

17 March 1979 Joseph Beuys co-founded the Grünen (Green Party) in Germany and in 1979, as their candidate, expressed his belief in art’s intrinsic connection to life and ability for creativity to “reshape our lives meaningfully.”

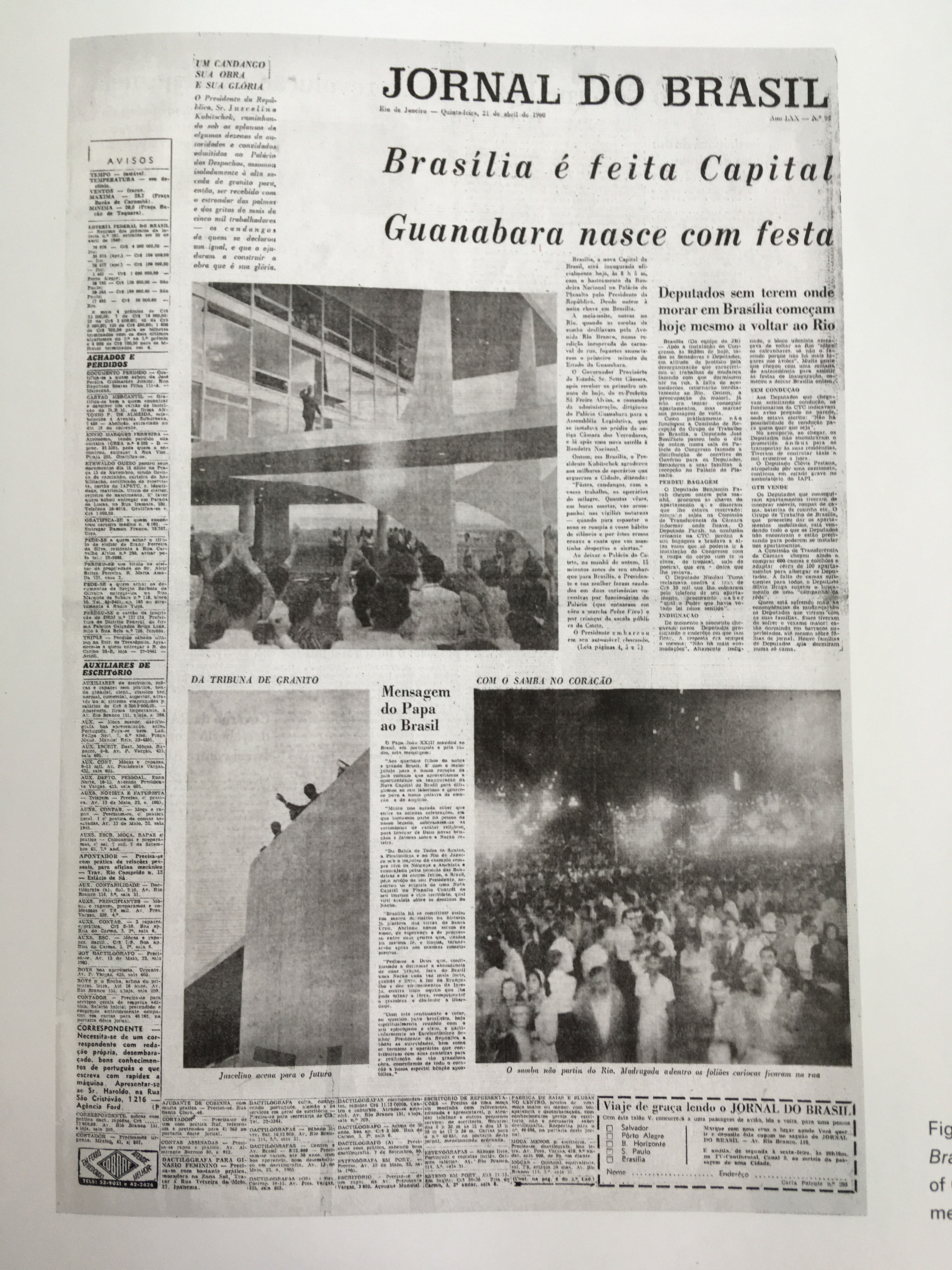

In the passage below, Princeton academic Irene V. Small discussed Neo-Concrete artist, Willys de Castro politicising of blank space. Small refers to Willys' redesign of the front page of the Brazilian newspaper Jornal do Brasil, in 1960, to include areas of blank space, highlighting the relationship between visual space, economics, politics and aesthetics.

“The redesign made clear that while space can be put to many uses, its common denominator was price. By formally revealing the economic space of advertising and the blank space of aesthetics as figures of equal value, de Castro starkly visualized the economic structure of the news.”[1]

I am hopeful that the deliberate modesty, organic materiality and adaptability of my felt artworks are reflective of the idealism associated with the historical beginnings of non-Objective Art, the meaningful environmentalism of Joseph Beuys and the aesthetic implications of the South American Neo-Concrete artists. These motivating factors together with their painted centres and curving forms, present a continuing investigation of what painting can be in the 21st Century.

[1] Jornal do Brasil, April 21, 1960 in Irene V. Small, Hélio Oiticica Folding the Frame, Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2016, p.47.